Introduction

An Extension of Time clause is an express provision that considers the adjustment of the contract date for completion in defined circumstances. Common law does not grant the owner or the contract administrator any implied power to extend the time allowing the contractor to fulfil its obligations. (Trollope & Colls Ltd v North West Metropolitan Hospital Board).

The main purpose of extension of time clause is to give the contractor more time for the completion of its work and consequently relieving the contractor of the obligation to pay liquidated damage or general damage for being late. In addition, this clause is beneficial to the owner by allowing the owner to grant the contractor more time for completing the works due to the delays caused by the owner, preserving the owner’s entitlement to liquidated damages for any delay caused by the contractor. (Peak Construction (Liverpool) Ltd v McKinny Foundations Ltd).

Types of delay

The delays that may entitle a contractor to an extension of time can be categorized as:

a) ‘Contractor delay’ – Delays resulted from the conduct of the contractor:

This type of delay is caused by the contractor’s own poor management. In case of a contractor delay, usually an extension of time is not granted for the completion of work in relation of that delay.

b) ‘Owner delay’ – Delays resulted from the conduct of the owner:

There are two types of owner delays. The first type is a delay caused to the contractor as a consequence of the owner’s breach of the contract or an obligation. For example, when the owner is required to provide design information to the contractor in a certain timeframe specified in the contract, but the owner fails to do so, the contractor may be entitled to an extension of time if it can establish that the delay in providing the design information in fact, delayed or was likely to delay the contractor in completing its work. (Leighton Contractors (Asia) Ltd v Stelux Holdings Ltd (2004)).

The second type of owner delay is where the owner or its agent lawfully instruct the contractor to perform additional work and consequently, the contractor’s work is delayed. This may be a ground for the contractor to be entitled to an extension of time.

c) ‘Neutral events causing delay’ – Delays resulted from matters raised out of other reasons but not related to the conduct of either the owner or the contractor:

Neutral events could include adverse weather, fires, force majeure events, as well as delays caused by third-parties such as strikes, delays caused by failure to get necessary approvals, and any other cause beyond the reasonable control of the contractor. There are no legal rules requiring one party or the other to bear the legal risk of the occurrence of a neutral event which causes delay to the contractor’s work. Therefore, whether the contractor is entitled to an extension of time due to a neutral event is a matter for the parties to decide.

d) ‘Concurrent delay’ – the contractual consequence of a project being delayed by the simultaneous operation of (a) a delay for which the owner is responsible; (b) a delay for which the contractor responsible, usually falls to be determined by the extension of time mechanism used in the relevant contract.

Where the respective delays are of equal causative effects, the consequence may be that the contractor is entitled to an extension of time because of the delay for which the owner is responsible, notwithstanding that the contractor was also simultaneously in culpable delay. Although there is no legal impediment for a contract providing that in such a case, the contractor is not entitled to an extension of time, it is unusual for a contract to provide that in the case of a concurrent delay, the assessment of the contractor’s entitlement to an extension of time is to be resolved by identifying “dominant” causes.

Under the Australian AS 4000-1997 form, when it comes to assessing an extension of time application in respect of a period of overlapping delays, the administrator is positively required to apportion the resulting delay according to the respective causes’ contribution to the delay. There are three important points to consider regarding concurrent delays:

a) Where a main contractor’s works are delayed by the default of more than one subcontractor, and each subcontractor is equally at fault for the delay, the subcontractors will be held responsible to the main contractor in equal measures.

b) Where a main contractor’s works are delayed by the default of more than one subcontractor, and it is not easy for the court to determine to what extent each subcontractor has contributed to the main contractor’s overall delay, the court may attempt to assess the relevant responsibility of each contractor.

c) The way in which delaying events are treated under a contract, depends on the applicable contractual terms.

Contractor’s duty to mitigate delay

The provisions of extension of time usually prevent the contractor from claiming the extension of time for a particular period of delay that the contractor could reasonably have mitigated or eliminated the effects of the delay. (John Mowlem & Co plc v Eagle Star Insurance Co Ltd (No 2)(1995)). In other words, when a contractor is entitled to an extension of time, but the contractor failed to mitigate the event due to its unreasonable conduct, that period of delay (which could be mitigated) is considered as the contractor’s conduct.

Float

Float is a period of delay which will not have the effect of delaying completion of the works or succeeding activities. Basically, an activity can be in float where it is not on the critical path. “Total float’” refers to the difference between a contractor’s planned early completion date and the contract date for completion. A party ‘owns’ float where it is entitled to delay or cause delay to an activity without the other party being entitled to claim relief for the delay.

Case Study:

The case of Glenlion Construction Limited v The Guinness Trust (1987) concerned a contract for residential development at Bromley, Kent. The contractor was delayed in achieving completion by the target date in its program which was before the agreed date for practical completion.

The contractor argued that where a program showed a completion date before the date for completion the contractor was entitled to carry out the works in accordance with that program and complete on the earlier date.

The court held that a contractor was entitled to complete on an earlier date, but there was no implied term obliging the principal to perform the agreement in a way which would enable the contractor to complete the works by the earlier date in the program.

Claiming an extension of time

Generally, if the contractor’s works are delayed or are likely to be delayed, the contractors are obliged to notify the contract administrator of the circumstances. It will be the responsibility of the contract administrator to review the information provided and determine whether it is appropriate to grant an exemption of time.

Notice of delay

Where a contract requires a contractor to give a notice of delay, the contractor is obliged to give a notice of delay regardless of the cause of the delay and the responsibility for the delay. The terms may specify that the notice must be given within a specific period of the occurrence of the delaying event. The content of the delay notice and level of information to be provided in the notice depends on the terms of the contract where it might be as simple as notifying that an even has occurred or provide the contract administrator as much as information. (London Borough of Merton v Leach(1985)).

Where a contract permits a contractor to claim an extension of time, the contractor needs to notify the contract administrator of the period of delay suffered and request for a reasonable extension of time. In situations where the contractor’s notice does not explicitly request an extension of time, yet it is clearly implied that the contractor provided the notice for that purpose.

If a contractor fails to give notice of delay where it is contractually required to do so, the failure may have the effect of disentitling it from subsequent claim of an extension of time or if still entitled to the claim, the assessment of the claim may be reduced to take the account of the contractor’s breach of obligation.

Case Study:

InAustralia Development Corporation Pty Ltd v White Constructions (ACT) Pty Ltd (1996) a contractor claimed that it was entitled to extensions of time for completion of its works. The extension of time clause provided that the contractor shall notify the owner within 30 days of when the contractor reasonably believed that delay had occurred. Giles CJ Comm D held that this operation operated as a time bar, so as to prevent the contractor from claiming an extension of time if notification was not given within the 30-day period.

Case Study:

In Peninsula Balmain Pty Ltd v Abigroup Contractors Pty Ltd [2002] NSWCA, Peninsula (principal) contracted with Abigroup (contractor) for the construction of a home unit development under a modified version of standard form contract AS2124-1992. The contract required Peninsula to ensure that the superintendent acted honestly and fairly in exercising its functions under the contract. Disputes arose and Abigroup was late in completing the works and the contract was terminated by Peninsula.

The contract’s extension of time regime required Abigroup to ‘promptly notify the superintendent in writing with details of the possible delay and the cause’. Abigroup was only entitled to an extension of time for practical completion ‘if within 28 days after the delay occurs it gives the superintendent a written claim for an extension of time for practical completion setting out the facts on which the claim is based’.

The superintendent also had power under the contract to extend the time for practical completion for any reason. This was even if the contractor was not entitled to an extension of time. The superintendent extended the date for practical completion, and no other extension was sought by Abigroup or granted prior to the date of termination of the contract.

The court found that the power to extend time without a claim was not just for the benefit of the principal but could be exercised for the benefit of both parties. The superintendent is obliged to act honestly and impartially in deciding whether to exercise this power.

Assessment of a claim for an extension of time

In circumstances where a contract administrator assessing applications for extension of times and the contract administrator has a discretion as to the period of any extension, it will usually be required by the contract to grant an extension for such period as may be ‘fair and reasonable’ for both parties. Therefore, if a contractor is instructed to perform additional work leading to prolonging the contractor’s work period, the contractor should usually be entitled to have a further reasonable time to execute the additional works. However, if a contractor’s affected works were in float at the time of the delay and remained in float, the contract administrator, the contract administrator will be entitled to refuse the grant of extension of time at least until those works become critical.

A construction contract may grant the administrator the power to extend the time for completion even if the contractor has not validly claimed an extension of time. In this situation, the administrator is expected to act honestly and impartially in deciding whether to exercise the power and if so, how it should be exercised.

Time limits for assessment

Usually, the contracts require the administrator to provide prompt response to the contractor’s extension of time claim or response within a specified period. If a contract does not provide a specific time, the implication will be that the administrator will be required to decide within a reasonable time which includes investigation of the relevant facts. (Perini Corp v Commonwealth (1969)).

If the administrator fails to complete an assessment within the period requested by the contract, there may be a number of possible legal consequences:

- The owner may be disentitled from claiming liquidated damages for late completion in circumstances where an extension of time ought to have been granted but was not granted. (Hawl-Mac Construction Ltd v Compbell River(1985)).

- When the administrator failed to exercise his discretion to grant an extension of time and the contract has no mechanism for correcting the failure by the administrator to fulfil his obligation, a court may step in and determine the contractor’s entitlement. (John Barker Construction Ltd v London Portman Hotel Ltd (1996)).

- A contract may provide that if a contractor’s application for an extension of time is not assessed within a stipulated period, the contract is ‘deemed’ to be allowed the extension of time that is claimed. (Stuart Bros (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Posei Pty Ltd (1993)).

- If the administrator purports to grant an extension of time ‘after’ the time by which the extension should have been granted, the putative granting of an extension will be of no effect and the administrator cannot claim to himself any power for which the contract does not provide. (Anderson v Tuapeka County Council(1900)).

- It may be possible for the contract administrator to grant an extension of time by utilizing any independent power even if the administrator has not granted an extension of time within the period prescribed by the contract.

If a valid extension of time was not granted to a contractor for a particular period, it does not automatically entitle the contractor to recover damages from the owner. The contractor may simply have a valid defence to any claim brought by the owner against the contractor in respect of the period in question. (Lim Ting Guan v Goodlink Enterprise (2004)).

Proof of delay and techniques for analyzing delay

The law does not mandate the use of any technique for the proof of delay in court or similar proceedings. Basically, it is a matter for an individual litigant as to how it presents its case as to the cause, effect of and contractual responsibility for a delay.

There are several techniques that are potentially available to parties to demonstrate the existence and effects of delay. Regardless of what technique is used, what matters is whether the evidence of delay, which is preferred presents a rational, coherent explanation of the delay.

Critical path method (CPM)

A critical path is a concatenation of activities identified in a construction project, delay to which will have the effect of causing delay to the completion of a project or a milestone. The very last item that need to be carried out before completion of a project will always be an item on the critical path. (Royal Brompton Hospital NHS Trust v Hammond (No 7)(2000)). At any one point in time, there may be more than one critical path and a critical path may change during a project.

Critical path method (CPM) involves the consideration of the effect of relevant events upon a critical path during the course of a project. CPM is a method often used in providing a persuasive explanation as to the causes of delay. Although CPM may be useful in assessing the impact of events on a project, it is not mandatory that a party use this technique in the presentation of its claim, unless this is a specifically required by the relevant contract or there is a direction by a court or tribunal that such analytical technique be used. The proper analysis and assessment of delay is usually based on the actual course of events on site, or to matters of common sense. There may be projects where CPM is not satisfactory way of analysing delay compared to some other methods. (Vivergo Fuels Ltd v Redhall Engineering Solutions Ltd[2013]). In general CPM can be deployed to identify the critical path at a given point in time and to review the course of the works in a completed project.

Case Study:

In Leighton Contractors Pty Ltd v South Australian Superannuation Fund Investment Trust(1995),

Leighton contracted to build a $35 million office building. The contract stipulated a date for practical completion. This was extended by the architect with a certified EOT, although Leighton contended that they were completed prior to this date. The contract provided for a contract program in the form of a critical path time scale network which Leighton was required to follow.

Leighton claimed, amongst other things, for costs of delays. Leighton contended that the introduction of the contract program and critical time path meant the EOT provisions did not apply and that a different procedure for EOT was implied.

Leighton produced a delay analysis, done by a process of computerized sequential modelling, which purported to demonstrate the effect of variations and other causes of delay and therefore an entitlement to costs based on a notional delay until the practical completion date.

The court held that, the process of sequential modelling disregarded the actual delay and took no account of actual events on site, such as the fact that actual progress did not keep pace with the program, nor of losses of time through non claimable delays due to inclement weather and industrial action.

The contract did not call for the production of a delay analysis after practical completion of the kind produced by Leighton. The contract authorized a claim for extension of time only if the progress was delayed due to specified events. Thus, there must be actual delay caused by a specified event.

Retrospective analysis

Retrospective analysis is usually adopted where assessment of an extension of time application is not made as to the actual impact of an event, but the determination goes to the likely effects of an event on the contractor’s works. In case of a contemporaneous application for an extension of time, a contract administrator may be required to issue a determination to a contractor’s entitlement of an extension within a limited period, rather than wait until the full effects of the delaying event are known. Some contract forms allow provision of new information about delay by allowing the administrator to review the subsequent effect of the event based on the later information obtained after the initial assessment.

Basically, a contract may provide that an extension of time application is to be assessed prospectively ( before the full effects of the delaying event are known), retrospectively (after the effects of an event are known) or both (Balfour Beatty Building Ltd v Chestermount Properties Ltd (1993)).

In subsequent arbitral or crucial proceedings, it is usually permissible to have regard to further information that has come to light to reconsider the contractor’s entitlement to an extension of time. Nevertheless, the terms of a contract may expressly provide that the contractor’s entitlement to an extension of time is to be determined having regard only to the relevant information available to the administrator at the time of the assessment and not on the basis of the information that came to light afterwards as to the actual effect of the delaying event. (State of Tasmania v Leighton Contractors Pty Ltd [2004]).

Application of the facts and the common sense

Even if the expert evidence that the parties have adduced as to the delays to a project, and the causes, durations and contractual responsibilities for the delays is deficient in some or numerous respects, the court may make its decision on such matters by reference to the primary facts put before the court by the parties, doing its best on the information available. A court is not obliged to accept expert evidence on delay where that evidence defies logic and common sense (De Grazia v Solomon[2010] NSWSC).

Financial consequences of delay

Delays for which the owner is responsible

These delays are as a result of intentional conducts on the part of the owner or its agent that causes the contractor to be delayed, with the consequence that the contractor incurs additional cost or suffers a loss. Generally, there are two categories of conducts that may give rise to monetary liability on its part.

The first category is where the owner or its agent has directed to the contractor to vary its work with the consequence that the time taken for performing the work is increased. This delay is different to the one caused by a breach of obligation on the owner’s part and therefore, the ability of the contractor to recover money is dependent on the contract conferring the contractor an entitlement to recover additional money.

The second category is where the contractor suffers delay leading to financial loss because of a breach of obligation on the part of the owner. In this case, the contractor’s claim may be substantiated based on (a) an entitlement to recover additional money under the contract; and (b) an entitlement at common law to recover damages for the breach of obligation. If a contractor is entitled to bring a claim pursuant to both contractual provision and at common law, will be required to choose between which remedy to pursue.

Loss and expense

Direct loss and/or expense refers to the financial consequences of delay and disruption. It may include but not limited to additional finance charges incurred as a consequence of delay, the net profit that the contractor would have earned for a relevant event, overheads and even the costs incurred by a contractor in preparing its claim for ‘direct loss and/or expense’ (Walter Lilly & Company Ltd v Mackay[]2012).

Clause 34.9 of the Australian AS 4000-1997 form confers upon a contractor who is entitled to an extension of time for a ‘compensable cause’ a right to claim delay damages. Accordingly, a claim for delay damages is not a common law remedy. It is a claim for compensation made pursuant to a contractual entitlement (Gantley Pty Ltd v Phoenix International Group Pty Ltd[2010] VSC).

Labour loss

In circumstances a contractor claims to have utilised additional labour because of a delay for which the owner is responsible and seeks for compensation, the onus is on the contractor to demonstrate that the use of additional labour resources occurred because of the delay. It is open to the contractor to rely on the labour estimate contained in its tender and measure additional labour resources against the tender (Decor Ceilings Pty Ltd v Cox Constructions Pty Ltd (No 2) [2005] SASC).

Plant and equipment

Where a contractor’s plant and equipment are rendered idle and non-productive as a consequence of delay, there may be an ‘opportunity cost’ to the contractor as the contractor would otherwise have been able to earn income from that plant and equipment while the income is foregone because of the delay. If the contractor intends to claim for loss of income, it must be demonstrated that the contractor mitigated its loss for example, by exploring the possibility of usage of its plant elsewhere during the period of delay (Driltech Ground Engineering Ltd v Group Plan Contracts Ltd [2001] HKCFI).

Where a contractor’s plant and equipment are detained on site due to an owner’s beach of contract that caused a delay, the contractor may be entitled to damages. There is no difference in situations where the owner wrongfully detained the plant and equipment or where the contractor is compelled to retain its plant and equipment on site. The legal objective in both cases is awarding the contractor sufficient measure of damages.

Subcontractor costs

An owner’s breach of obligation may cause delay not only to the main contractor’s works, but the work s of subcontractors engaged by the main contractor. In such circumstances, affected subcontractors may claim damages from the main contractor and those damages may be passed on by the main contractor to the owner and recovered as damages as a consequence of owner’s breach of obligation (Hadley v Baxendale).

Preliminaries

‘Preliminaries’ refers to the cost to a contractor of maintaining its site establishment. Costs such as hoarding or fencing for the site, site cabins, project insurance are considered as preliminaries. A prolongation of a project may lead to some time-related preliminaries increasing in amount. Therefore, a claim in relation to preliminaries’ costs as a consequence of an owner’s delay should identify the additional costs actually incurred due to the delay in question as opposed to applying a percentage or allowance based upon the contractor’s tender price (Lucas Earthmovers Pty Ltd v Anglogold Ashanti Australia Ltd [2019] FCA).

Off-site overheads

Off-site overheads or head-office overheads are indirect costs incurred by a contractor as part of its normal business operations. It may include cost of head office staff, lease payments, utility bills, insurance and many other costs. Where a contract’s works are delayed as a consequence of matters for which the owner bears contractual responsibility, the contractor may be entitled to recover off-site overhead costs attributed to the delay. Where the basis for recovery is a breach of contract on the owner’s part, off-site overheads may be recovered as damages.

Loss of profit

A contractor’s loss of profit is recoverable in principle where it is delayed as a result of the owner’s breach of contract, subject to adequate proof that the contractor has suffered a loss as a consequence of the project being delayed. The contractor’s turnover and profit accounting evidence in the previous years can be used to demonstrate the likely profit of the contractor expected for the period the delay occurred.

Delays for which the contractor is responsible

If a contractor fails to complete its work by the contract date of completion, it will usually be liable in damages to the owner. The usual remedy of an owner for the late completion by a contractor of the contract works is liquidated damages. However, if the liquidated damages are not agreed on in the event of delay, the owner will be entitled to recover general damages to the extent that they are capable of being proved.

In the case of a typical building project, the type of loss or damage that an owner may suffer usually include the loss of opportunity to take advantage of a completed building for a period and to realise its earning potential through disposition of use such as rental. Thus, an owner may be entitled to recover damages for loss of rental income (J & P Reid Developments v Branch Tree Nursery & Landscaping Ltd, 2006 NSSC). If the property is residential and not a commercial purpose, damages may be recovered for the loss of enjoyment and use of the property during the period of delay (Zeng v Leeda Projects Pty Ltd [2019] VSC).

Where a subcontractor’s breach of contract causes the main contractor’s works to be delayed and liable to the owner, the main contractor’s damage may in principle be recovered from the subcontractor.

Where a contractor’s delay causes the owner to forego revenue that would otherwise be earned from the asset that is subject to the contract in question, the owner’s entitlement is for damages reflecting its ‘net profit’ had the asset been completed on time and not the gross profit.

The Effect of Covid-19 on Extension of time claims and Frustration of contracts

The Common Law recognizes that a contract may be automatically terminated when the performances of the contract by the relevant parties are unable to be performed due to circumstances outside the control of the parties. The definition of this concept was first articulated in Davis Contractors Ltd v Fareham Urban District Council [1956] AC 696, as “without default of either party a contractual obligation has become incapable of being performed because the circumstances in which performance is called for would render it a thing radically different from that which was undertaken by the contract.” This was later accepted in Australian courts in the case of Codelfa Construction Pty Ltd v State Rail Authority of NSW (1982) 149 CLR 337.

Essentially, if the current circumstances have changed so significantly, from the inception of the contract, that the contract now would have a different affect and meaning, the contract will be frustrated and terminated. As per Codelfa, the main consideration is, “whether the situation resulting from the [allegedly frustrating event(s)] is fundamentally different from the situation contemplated by the contract on its true construction”.

This is to be differentiated from the concept of Force Majeure, which means that some event has occurred that is beyond the control of the parties, usually including war, epidemics and crimes, resulting in the contract’s termination. This concept has not been recognized under the Common Law but is commonly drafted within contracts. These Force Majeure clauses will allow both parties to terminate the contract when the specified event has occurred. The application of this law will depend on the construction of the contract between the parties. For example some standardized construction contracts have a Force Majeure clause but some do not, such AS 4000 and AS 2124.

Generally, the concept of frustration is narrow at law to include cases where one of the contracted parties has died or been incapacitated, the contract has become illegal or the contract matter has been destroyed. However, there may be scope to include the frustration of a contract where it may be possible to complete the contract but the common purpose of the parties to the contract has become frustrated.

This can be significant when viewing construction contracts that have been affected by time delays and in particular time delays due to Covid-19. For example, there may be a difference in law between a delay in completing a contract that lats for a short time as opposed to a longer time. For example, in Metropolitan Water Board v Dick, Kerr & Co Ltd [1918] AC 119, a 6-year contracts that was delayed for over 2 years was considered to be frustrated. However, in the case of National Carriers Ltd v Panalpina (Northern) Ltd [1981] AC 675, a delay of 18 months, that allowed for the party to continue operating for the following three years was not considered to frustrate the contract.

When considering how this may apply to construction contr5acts that have been affected by delays due to Covid-19, the first step would be to consider if there were any Force Majeure clauses in the contract. The affect that they have will depend on their construction and whether a global pandemic would fit within their scope.

The Affect of Covid-19 frustrating a contract may be harder to establish, as the frustrating circumstances must not merely cause an inconvenience but must make the performance of the contract impossible, as per Davis Contractors Ltd v Fareham Urban District Council [1956] AC 696. Otherwise, the delay in the contract would likely be covered by a time extension clause within the contract.

Different types of standard construction contracts

There are several construction contracts that are commonly used in Australia when commencing a construction agreement. These standardized contracts act to make the process of commencing a construction contract easier and with familiarity. Although, they are commonly altered and amended by both owners and contractors.

One of the more common contracts, are those that were made by Standards Australia Limited, a non-for-profit group, whose standardized contracts are recognized by the government. They include;

- the AS 4000, for construction contracts only;

- the AS 4300, for construction and design;

- the AS 4902, for construction and design;

- the AS 2124, for general conditions of contracts and

- the AS 4906, for minor works conditions of contracts.

Additionally, there are contracts that are made by the Master Builders Association and the Housing Industry Association, although these construction contracts usually favour the builders.

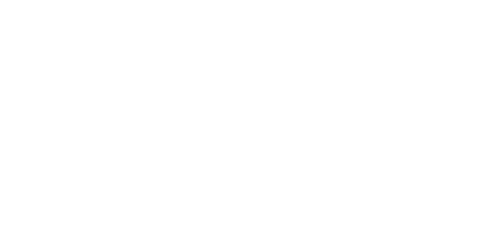

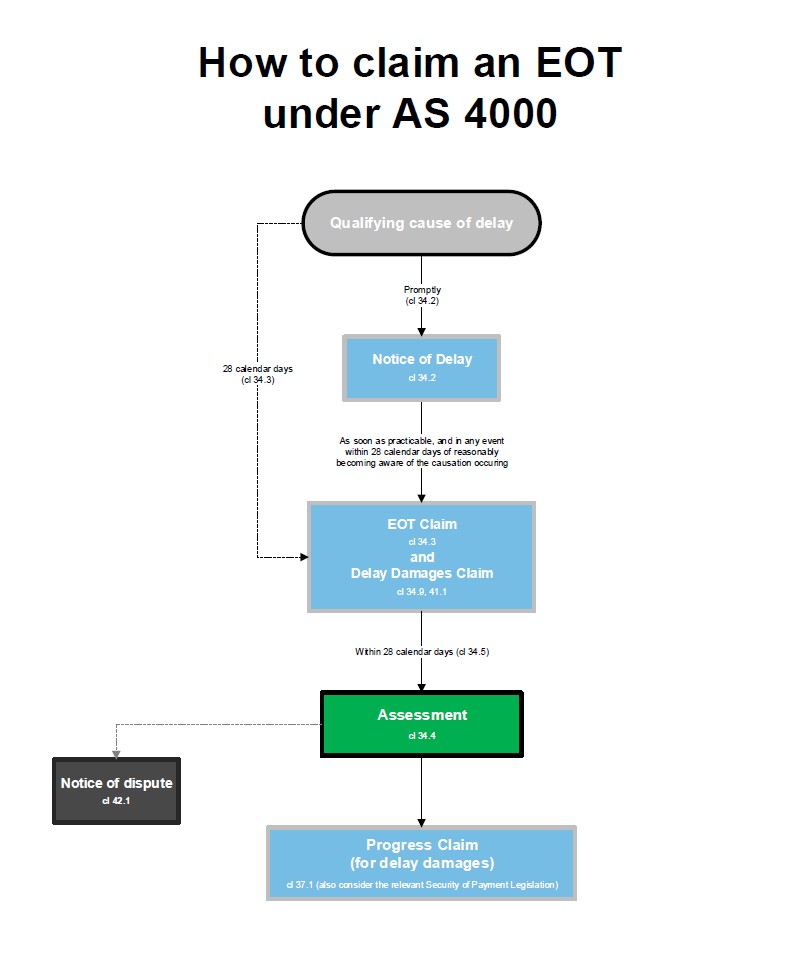

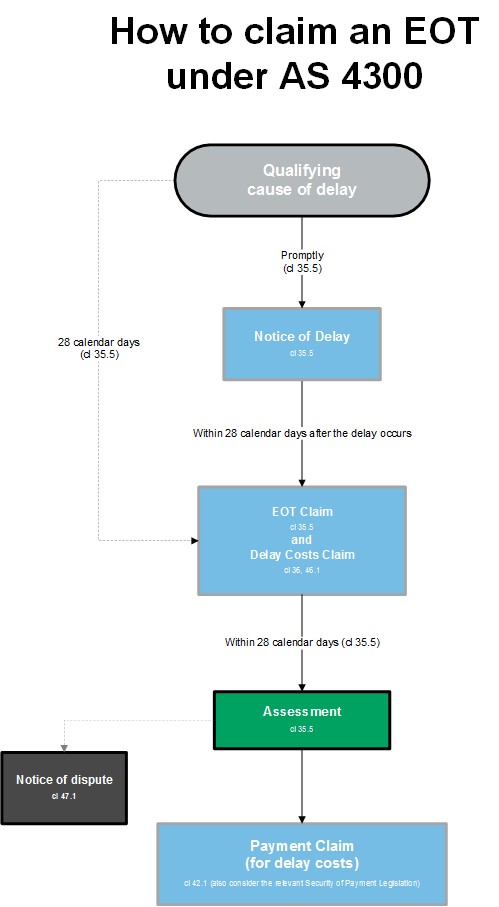

Flow Diagrams for extension of time in contracts

AS 4000 Contract – Contract for Construct only

Source: https://www.turtons.com/blog/how-to-claim-an-eot-under-as-4000

AS 4300 – Contract for design and construct

Source: https://www.turtons.com/blog/how-to-claim-an-eot-under-as-4300

AS 4902 – Contracts for design and Construct

Source: https://www.turtons.com/blog/how-to-claim-an-eot-under-as-4902

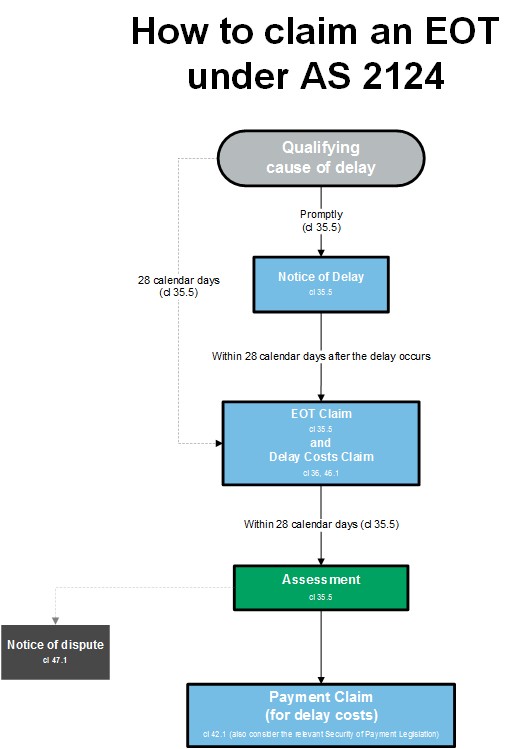

AS 2124 – General conditions of contract

Source: https://www.turtons.com/blog/how-to-claim-an-eot-under-as-2124

Liquidated damages

It is important to note that often within construction contracts, there will be a liquidated damages clause. This type of clause in a construction contract is an express provision whereby the parties agree to a pre-determined amount of money that will be payable to the other party if there is a breach of contract. This serves to put the owner back into the position they would have been in but for the breach of contract. This clause can be triggered when there is a breach of the contract, although it will depend on the construction of each particular contract.

Often this clause will be triggered where the contractor has not practically completed their part of the construction at the time specified in the contract, which may include after a given grace period. This includes the updated end times that have come after a successful extension of time claim. Sometimes the contract will provide provisions that allow for an administrator to issue a certificate that the contract has not been fulfilled, to trigger the liquidated damages clause. The owner would then issue a certificate to the contractor stating that they intend to claim liquidated damages in respect of certain period.

However, these damages will usually be limited to the actual monetary loss that has been suffered by the owner, because of the contractor not completing their work. This can be beneficial to both parties, as the contractor is limited to the liability stipulated in the contract and the owner can easily receive their due damages.

It is therefore crucial for both owners and contractors to have carefully constructed contracts when initiating their construction proceedings, as this can be very significant in the case of a breach of contract. further, when a contractor seeks to obtains an extension of time to their contract, they should be aware of the new completion date, as failing to complete the work by that date may result in significant damages.

Latent conditions causing delay

Latent conditions causing delay refers to unforeseen conditions at the site of the construction that have the ability to cause delay to the contractor and disruption to their work. This may include the quality of the ground being used or other such defects that can cause a delay in time or additional costs being incurred. This may be because the contractor has unforeseen tasks that must be completed to fulfill the task properly or there are statutory requirements pertaining to, for example, a contaminated worksite, that causes delay to the contractor.

The starting point in ascertaining how these unforeseen conditions affect the parties is the applicable contract itself. This will lay out the terms of dealing with such events. This could be categorized as the parties allocating the risk of unforeseen conditions between themselves via their contract.

Some standardized contracts have clauses within them that identify the methods of dealing with a latent condition that causes delay. For example, AS 4300 has clauses that allow the contractor to apply for a time extension in the scenario where a latent condition causes delay.

For more information, please contact Warlows Legal using the contact information below.